He had the gift of revealing each individual's talents and had won their respect and belief in his work. To be in one of his ballets, even at the humblest level, was seen as a special bestowal of regard and made you one of a select, elite chosen few.

Throughout his creative career, Kenneth MacMillan was concerned with making ballets which explored the human condition. Even his early works sought to expose mental and physical anguish, sexual needs, through movement which became more assured and innovative.

He was rebelling against the conventional idea that ballet was light entertainment…He was saying that ballet can be like theatre, like cinema, it can tell you about your life, about other people’s lives, it can express things that are inexpressible in words.

MacMillan took the gritty realism accepted in theatre and shoved it into the fairytale decorum of ballet.

Kenneth made each dancer an integral part of the creative process, encouraging and stimulating the imagination to the limits, searching the soul for verity, no false airs and graces, no sentimentality, no pasted-on emotions. He wanted raw, gutsy, unattractive humanity out of which true aspects of the human condition could emerge. This kind of psychological delving and digging was not common practice in the ballet world of those days. With Kenneth we all felt like privileged scientists, pioneers opening hitherto unexplored territory and at the very forefront of innovation.

Dance Open 2016:

«Romeo and Juliet», Perm Ballet

Kenneth MacMillan in his own words

I turned to choreography as a release from dancing and I was lucky enough that the first thing I did everyone liked.

What I wanted to put on stage had to have more reality than much of what I was seeing in the 1940s and 50s… Ballet looked like window-dressing. I wanted to make ballets in which an audience would become caught up with the fate of the characters I showed them.

It is very English — you mustn't show emotion, and I think my ballets embarrass people because I let emotion out.

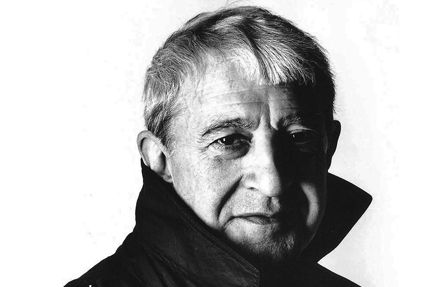

Kenneth MacMillan

(1929-1992)

Оne of the leading choreographers of the 20th century. Coming from a poor British working-class family he went up to become a legend in the world of ballet, the first choreographer who included psychological insight and expressive choreography language in the classical decorations. Some of MacMillan’s inspirations included Lynn Seymour, Christopher Gable, Monica Mason, Marcia Haydée, David Wall, Darcey Bussell and Irek Mukhamedov. Throughout his choreography career MacMillan created over forty ballets, winning the respect and admiration of dancers worldwide. His main focus was on long ballets: no other choreographer of the 20th century has produced so many full-length works.

MacMillan entered the world of big ballet at the age of 15, when he forged a letter from his father to Ninette de Valois, requesting an audition with her. The audition went really well and MacMillan was awarded a scholarship at Sadler’s Wells School, later joining the Company. Although he enjoyed great success as a dancer, he could never fully overcome stage fright and this was one of the reasons why he turned his hand to choreography at only 23.

MacMillan first choreographic work, Somnambulism, a ballet set to jazz music by Stan Kenton but based on classical technique, staged for the Sadler’s Wells Theatre in 1953, demonstrated that there was a new and highly individual talent emerging. It was at that time when MacMillan began to create for The Royal Ballet; his early one-act ballets included The Burrow (1958), The Invitation (1960) and The Rite of Spring (1962), in them MacMillan managed to express the feelings and anxiety of the post-war generation, something new and unusual for the ballet of that time.

In 1965, MacMillan staged his first full-length ballet, Romeo and Juliet, for the Royal Ballet Principals Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable. However, the honour of the first performance had gone to Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn. Other full-length MacMillan’s productions for the Royal Ballet include Gloria, Manon, Mayerling and Requiem.

Apart from the Royal Ballet, MacMillan worked for the Deutsche Oper Ballet Berlin, American Ballet Theatre and Houston Ballet. MacMillan died unexpectedly on 29 October 1992 backstage at the Royal Opera House during a performance of his ballet Mayerling.

Festival Team: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Tickets: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Accreditaion and Cooperation: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.